For me, photography is a way to slow things down, to hold on to moments that I recognize as being otherwise impossible to possess.

My photographs exist as a record in light of how I was seeing and feeling in a particular time, at a particular place: a specific moment of my life. A moment which I am truly and almost painfully aware will never be mine again. Photography is my method of making a mark on the whole of existence – to express and compress the entirety of who I am into a single 6×6 frame with each depression of the shutter button. It is time and life and light made tangible.

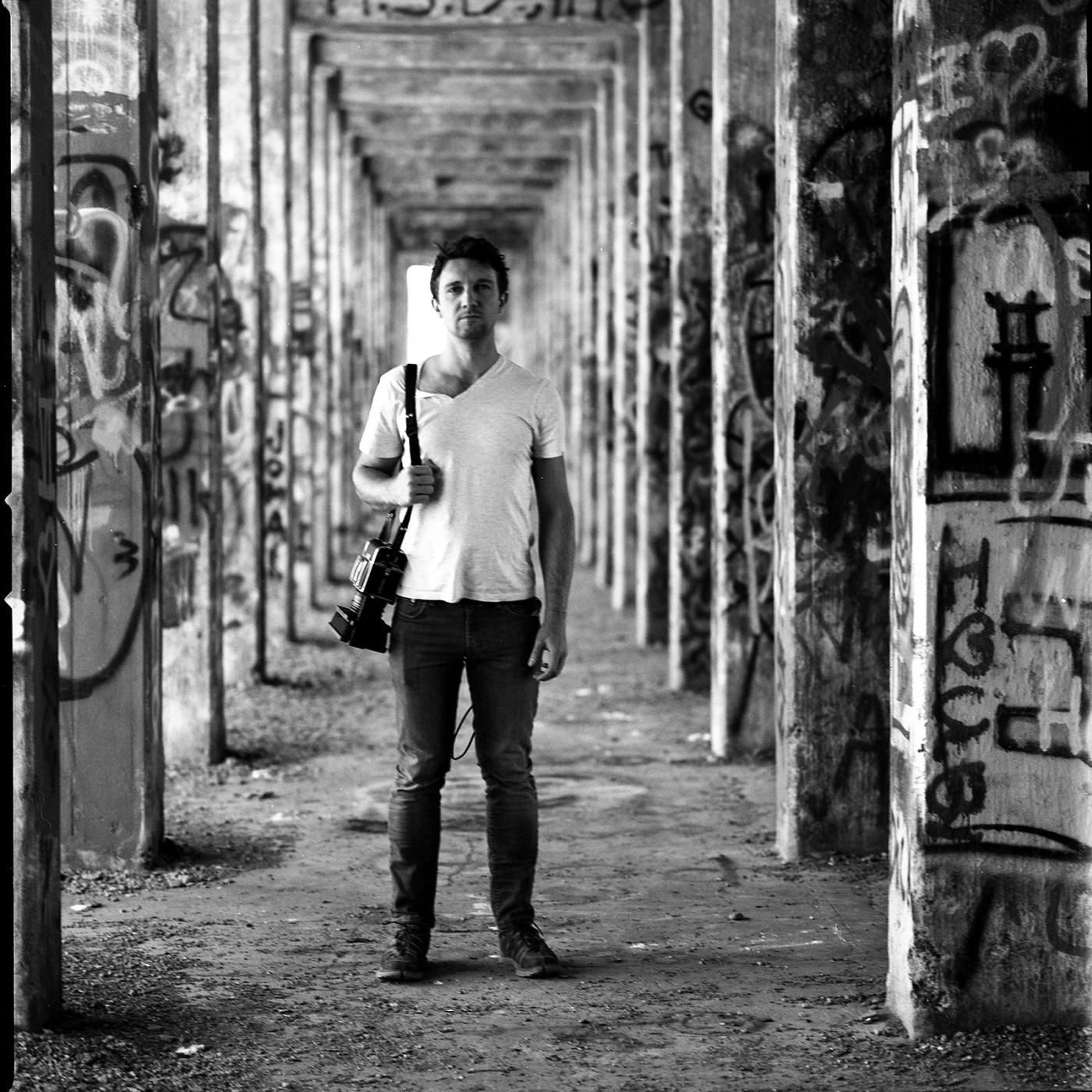

The reason I shoot film in the age of the DSLR, the CMOS sensor, 16-bit RAW, four-hundred-and-nine-thousand ISO, and 61 points of phase-detection autofocus is simple: it is analogous to choosing your feet as a mode of transportation rather than the automobile, to spending an evening preparing a meal for your family instead of going out to a restaurant, or designing and building something yourself when you could have just purchased it. It is about the process. The end result and its comparison to a digitally captured image is a matter of taste, and effectively irrelevant.

“Every frame carries a certain weight, a certain deadly-serious importance.”

A film camera and all of it’s “limitations” only serve to bring you, the photographer, closer to the process of creating a photograph. In the absence of autofocus, of in-camera metering, of aperture-priority, auto-ISO and especially the ability to instantaneously review your work, something interesting happens: you are forced to truly know your craft. Your success in creating even a single successful image relies entirely on your knowledge of photography and of the capabilities and limitations of the tool in your hands.

You must slow down. You must consider your subject with regard to its size, shape, relationship to other forms, and the light those forms are reflecting back into the lens. With film, there are no do-overs. You cannot delete the photons you’ve just exposed to those light-sensitive silver-halide crystals. That decision – all of your decisions in the process – are now permanent. And that moment, my friend, is gone. Film brings the process of creating an image closer to you – and closer to your heart. Every frame carries a certain weight, a certain deadly-serious importance. This importance carries through, from the moment you load the camera until when, sometimes weeks or even months later, you see the end result. The sensation is sublime.

To be fair, I must admit that I do own and shoot with a digital camera. I’ve recently invested in a Sony a7S and honestly, I love it. Digital cameras have strengths in certain situations where my Hasselblad would be impractical and ineffective. However, as long as you possess a strong understanding of your camera system and its limitations, I believe you can make it work no matter what the content or situation. In the end, I prefer my Hasselblad for more contemplative photography and especially in situations where extreme resolution is preferable. The Hasselblad 500CM is undoubtedly my favorite camera, and my single most prized possession. It is not amateur friendly, to say the least: It lacks autofocus, there is no internal metering or automatic frame advancement. While specialized and unwieldy, it is an absolute masterpiece with regards to design and photographic precision. The process of using it, to me, captures the essence of skilled photography.

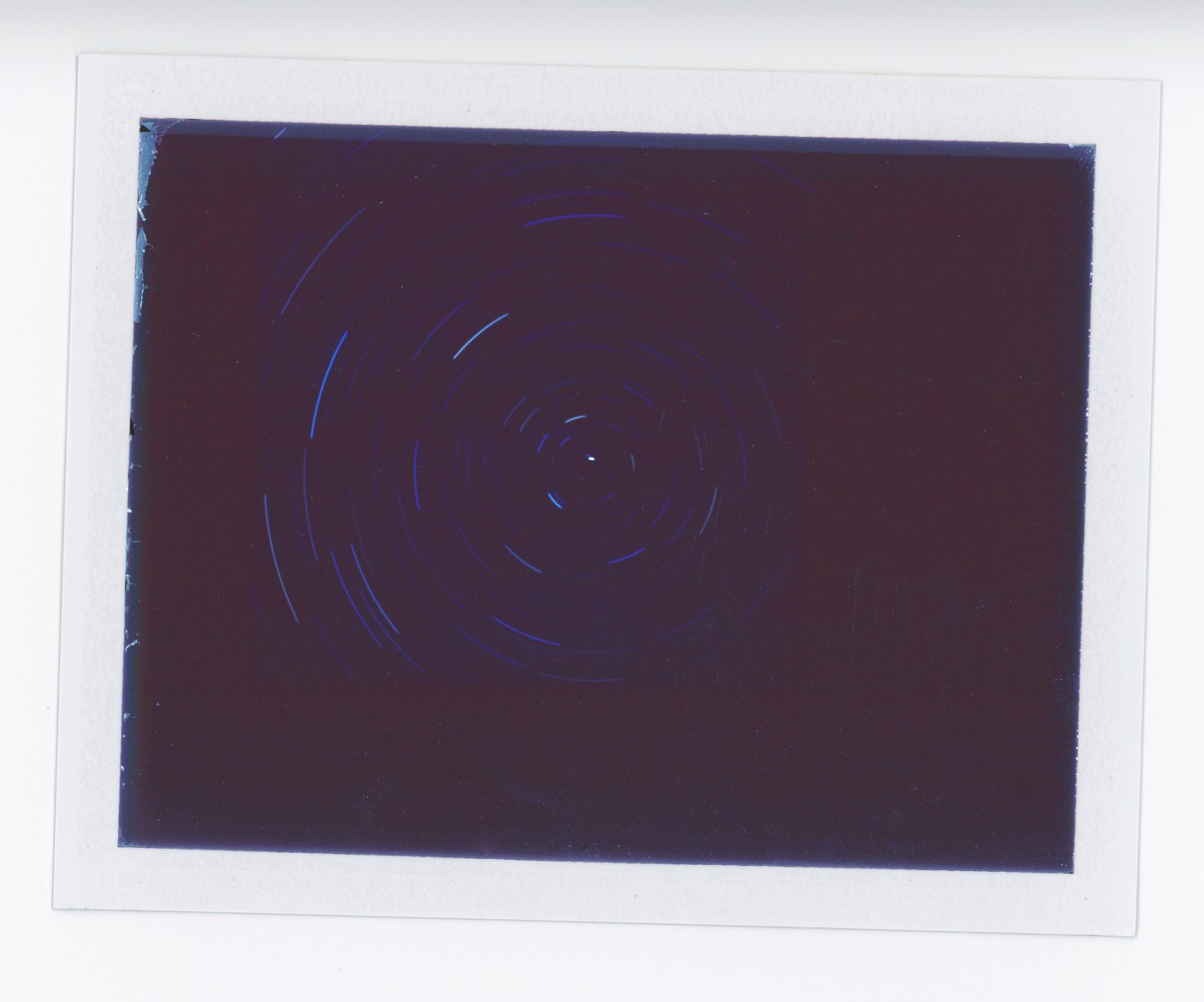

I prefer to shoot slow speed films for their fine grain, so photographing the Milky Way is an impossibility. Star trails are the only logical option. In this regard, film has one distinct advantage over its binary-based rivals – I do not have to worry about the extreme amount of noise invariably generated by the electronics of digital cameras during very long exposures. There will be no need for image-stacking to reduce or eliminate noise, nor will there be any hot pixels. I am free, and in fact incentivized, to expose for as long as possible. As a consequence, even when using instant film, I don’t get to make any test images. I have to set a frame, release the shutter and leave the rest to chance. Contrary to what you might think, it actually makes the process a whole lot less stressful.

To aim your camera upwards is to capture the mystery that surrounds this single inexplicable bastion of humanity we call the Earth. It is an expression in film of the energy of photons sent streaming through space, hundreds of millions of years ago by stars perhaps long since expired . I’m not sure there is any subject less self-absorbed, more honest, optimistic and curious than the night sky as viewed from Earth.

I hope, through my continued work with photography, to always be approaching absolute, unfiltered truth with regards to how things are and how I am experiencing them. I hope to continue capturing images as I see and imagine them. Sometimes this will mean carefully planned and executed studio work, and other times it will require that I continue putting myself into situations where the light and forms spontaneously come together, asking me to photograph them. I believe the best thing you can do as a photographer is to continue putting yourself into new situations. Take road trips, instigate adventures, and take opportunities to travel whenever they present themselves. After all, you never know when a frame will find you.

![]()

About the Author

Copyright Cody William Smith 2014. All Rights Reserved.

Disclosure

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites. We are also a participant in the B&H Affiliate Program which also allows us to earn fees by linking to bhphotovideo.com.

Learn Astrophotography

Astrophotography 101 is completely free for everyone. All of the lessons are available on the Lonely Speck Astrophotography 101 page for you to access at any time. Enter your email and whenever we post a new lesson you’ll receive it in your inbox. We won’t spam you and your email will stay secure. Furthermore, updates will be sent out only periodically, usually less than once per week.

Help us help you!

Believe it or not, Lonely Speck is my full-time job. It’s been an amazing experience for us to see a community develop around learning astrophotography and we’re so happy to be a small part of it. I have learned that amazing things happen when you ask for help so remember that we are always here for you. If you have any questions about photography or just want to share a story, contact us! If you find the articles here helpful, consider helping us out with a donation.

[button font_size=”16″ color=”#136e9f” text_color=”#ffffff” url=”https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr?cmd=_donations&business=lonelyspeckblog%40gmail.com&item_name=These+tips+help+keep+lonelyspeck.com+running.¤cy_code=USD&source=url” target=”_blank”]Donate[/button]

Thanks so much for being a part of our astrophotography adventure.

-Ian

Really wish you had exposure times under each photograph. About to go to Canada and shoot night with my Hasse.

Hey there Marc.

My bad. Let’s see.

The image at the top (Mt. Whitney Trail Camp) was about a 4-hour exposure if I recall correctly, I think at f/8.

The second image was maybe 2-3 seconds at an f/4.

The polaroid was about 45min – an hour at a f/5.6

I’m least certain of the f-stop, but the final image would have been about 2 – 2 1/2 hours at probably a f/5.6

Hope this helps. Happy shooting!

Oh! And my best advice (if I didn’t state it here already) is to find a frame you like and really commit! Obviously had less luck with the frames I pulled too early. With digital you can just keep trying stuff – opening up the lens and boosting the f-stop, chimping each time the LCD lights up again. Long exposures on film reward patience and commitment. Plus, they free you up to go enjoy your life (drink a beer around the campfire?) while the digital shooters are busy tweaking and shooting in an endless cycle.

Cody! This is awesome, I want to start shooting film and I am a fan of astrophotography, what start up set-up would you recomend?

Thanks for the inspiration. I think i’ll bust out my Canon AE-1 and see what I can capture in the night sky.